The Rebellion of Youth (1964–1991)

TOWARDS THE ROOTS OF THE NATION

Empires know how to cultivate contempt in small nations for their own memory.

Edmondas Kelmickas, poet and long-time resident of what was known as “Gorkynė” in occupied Vilnius (present-day Pilies Street)

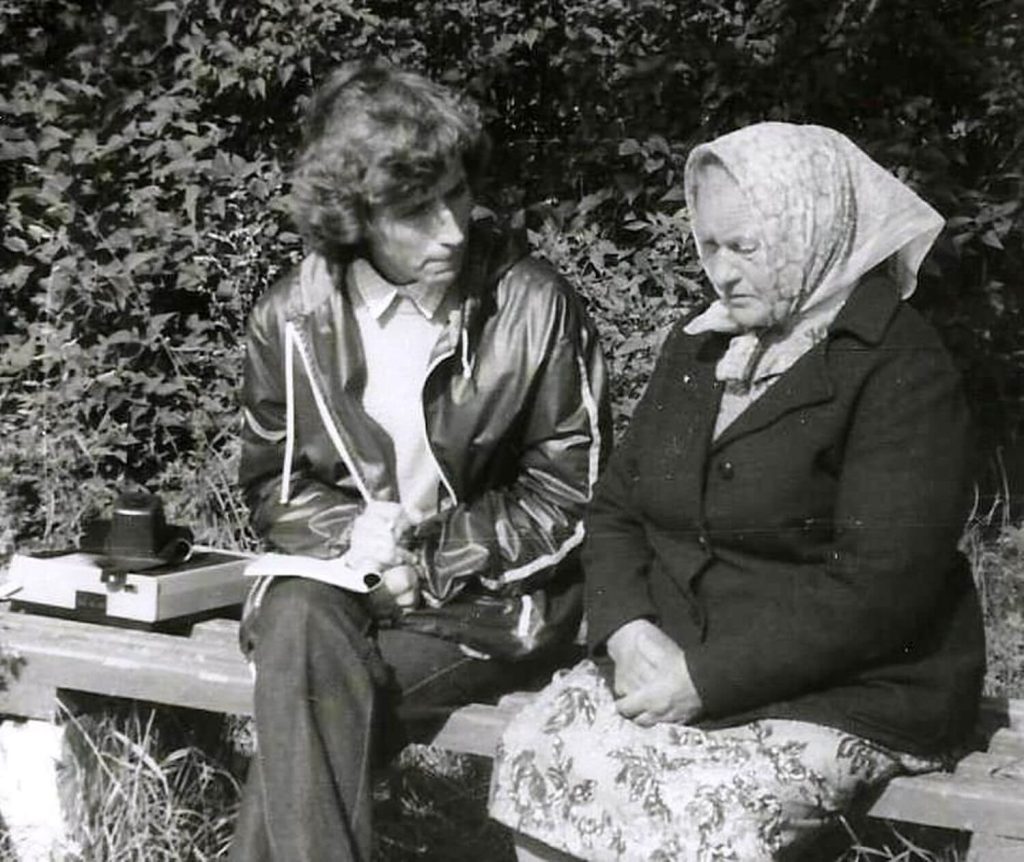

Then they gave us a lot of flak about why we were going to see the old ladies and singing those ancient songs and learning to sing. […] The Soviet system was really afraid of patriotic songs. […] “who started singing ‘Viens du trys, graži Lietuva’ (‘One, Two, Three, Beautiful Lithuania’) on a hill fort or a burial mound?” – KGB emissaries questioned Nijolė Balčiūnienė, head of the Gabija section of the Vilnius University expedition club, whom they had brought into their office for interrogation. The authorities upbraided the expeditioners: “What are you digging around Lithuania’s past for? Why do you visit hill forts?

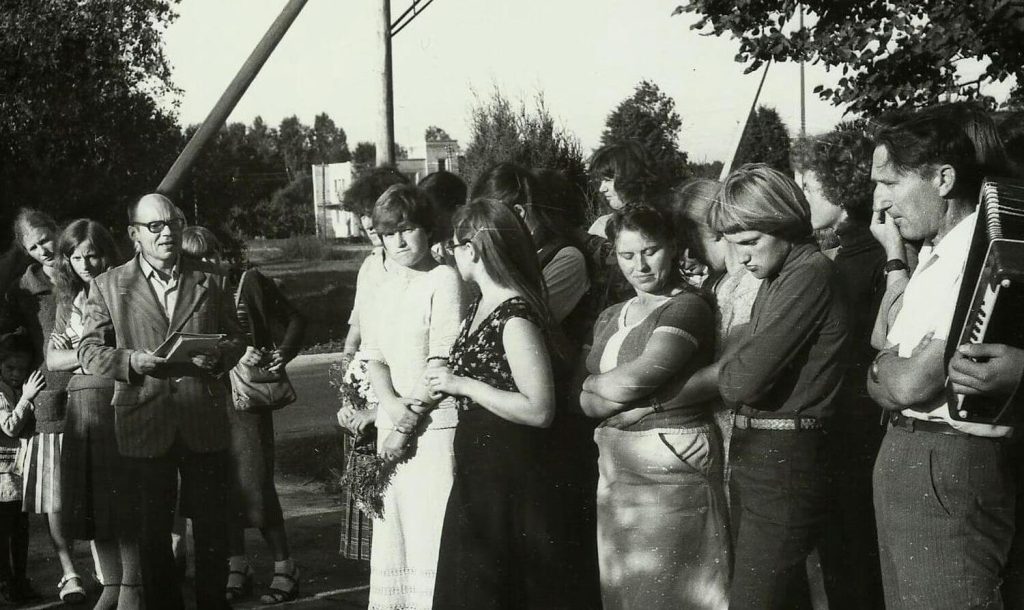

In the late 1960s, the famous Rasos (St. John’s Eve) celebrations began in Kernavė. The Ramuva Ethnographic Society was established in Vilnius, and the expanding expeditioner movement took to unprecedented mass campaigns not sanctioned by the government. News came out in 1969 that there were plans to demolish the birthplace of the legendary pilot Steponas Darius. In order to save it, several hundred expeditioners and aviators gathered in Judrėnai, in Dariškės (Klaipėda District), which was once burned down by members of the Soviet destruction battalions. On 9 May, they poured a burial-mound three metres high with their bare hands under the big oak tree in the yard of the homestead, dug up the foundations of the pilot’s original house, lowered in a capsule with wreckage from the Lituanica (airplane flown from the United States across the Atlantic Ocean by Lithuanian pilots Steponas Darius and Stasys Girėnas in 1933), built a stone wall, and hung a memorial plaque. The next day, the memory of Darius’s co-pilot Stasys Girėnas was honoured in his native Vytogala (Šilalė District).