The Rebellion of Youth (1964–1991)

PUNKS

It feels like it was yesterday. A period of cataclysms, garbage dumps, dirt, the dark Old Town of Vilnius, a totalitarian national surveillance machine, where every outcast was quickly spotted and extinguished…. It was the capital’s street culture that infected at least the Old Town of our capital.

Mindaugas Sėjūnas

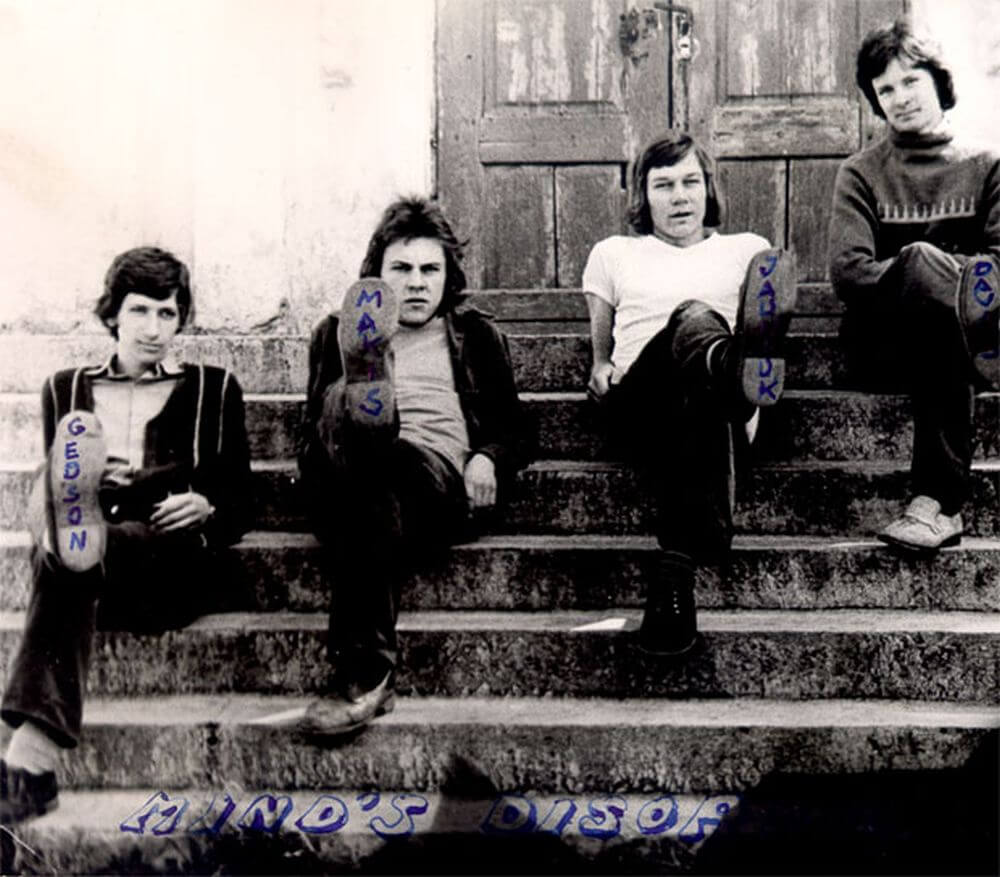

The first Lithuanian punk rock band – Mind’s Disorder, formed in 1973 at Vilnius Secondary School No. 22 (now the Vilnius Gediminas Technical University Engineering Lyceum). From left to right: Gediminas Simniškis-Gedson, Arvydas Makauskas-Makys, Jaunius Besenas-Jauniukas, Gintaras Davalga-Davas.

Vilnius, 1974. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Arvydas Makauskas)

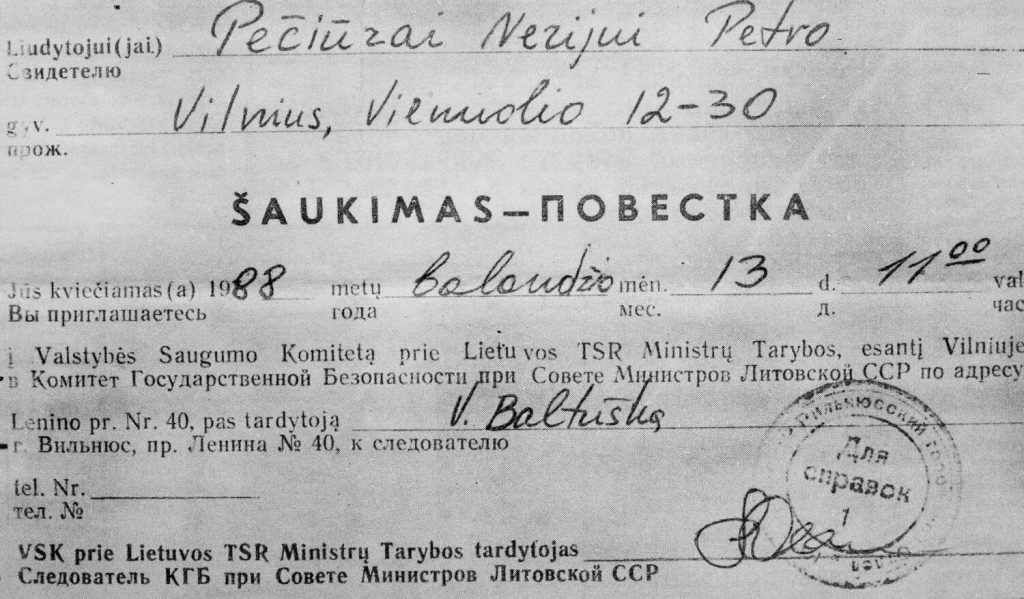

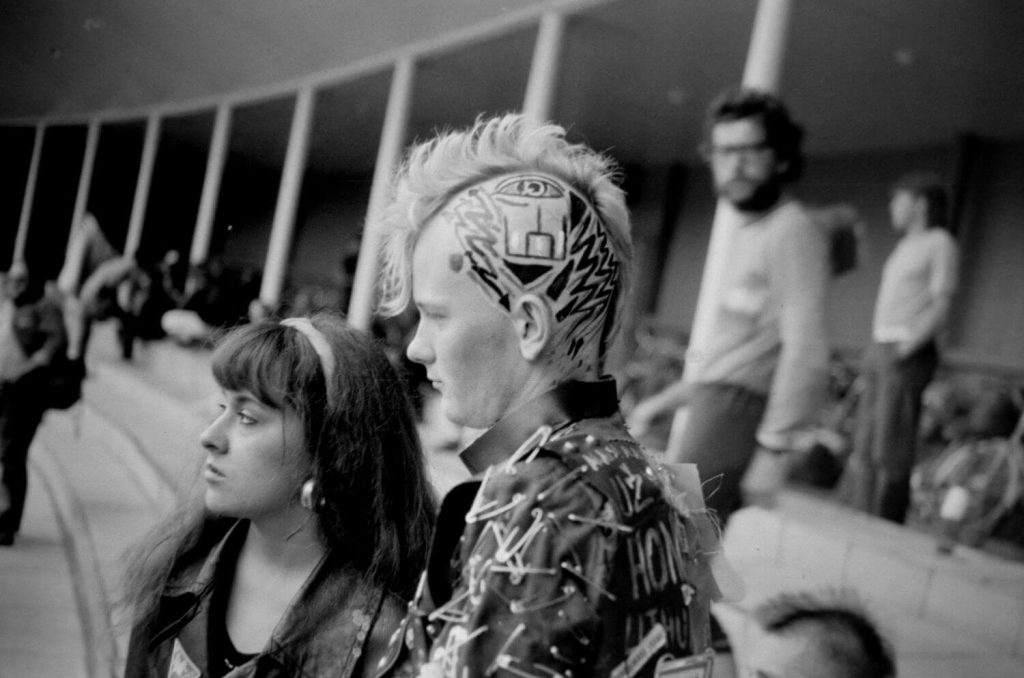

“[…] we punks are like walking flyers as it is,” Nėrius Pečiūra – the father of punk – once explained when he was posing for Gitenis Umbrasas, a fresco and mosaic student who was a kindred soul.

“First we’ll draw you, then we’ll paint you, then we’ll immortalise you in a fresco,” promised the artist, embellishing Pečiūra’s “unaesthetic” shaved head with a triangular purple stamp with the inscription MIASOKOMBINAT (Russian: MEAT PROCESSING PLANT).

The ideology of communism in Soviet Lithuania had reached the languishing stage and was begging for someone to put an end to it. The punks – the new generation of that time – became more impressive every month: they dyed their mohawks with peroxide, decorated their clothes and bodies with drawings, symbols and tattoos, wore leather jackets studded with rivets, and walked around in combat boots. With their appearance, brash behaviour and blaring music, this new generation broke up the routine of the decaying cities. Young people who glorified individualism and freedom started to challenge the double standards, lies, senseless obligations and violence. Unlike the peaceful hippies, these young rebels often stood up for themselves with their fists. How else could they defend themselves against “Urlaganai”, “Montanos” and other different-minded groups? One time, even the militiamen in their blue jackets ran away from the punks, calling in for backup. Militancy and audacity hid the inner world of the punks, which was often sensitive, fragile and sincere. Their futuristic nicknames, like Kablys (“Hook”), Varveklis (“Icicle”), Bliūdas (“Bowl”), Vazonas (“Flowerpot”), Varžtas (“Screw”), Maišas (“Bag”) and Trumpas Kaklas (“Short Neck”), were keywords of their characters. Freedom, boundless fantasy, a sense of humour and persistence were their saving grace in the most absurd situations of life. Vilnius punks used to gather near the Cathedral stones or in the so-called “dog park”, which is now the Presidential Park. They would sleep and drink there. The militia didn’t go there. The dog park was fenced in, but if you knew where the bar was broken in the fence, it was easy to sneak in.

Lithuanian punk rock songs resounded in the capital city, with the best ones written by Varveklis (“Icicle”) and Atsuktuvas (“Screwdriver”). Encouraging feelings experienced then and there turned into clumsy chords and metaphors: “I went bald from peroxide”, “A city full of drug addicts”, “Lithuania is a force”, “Today is glasnost – a lot is possible, talk about the future – with the heart to Stalin”.

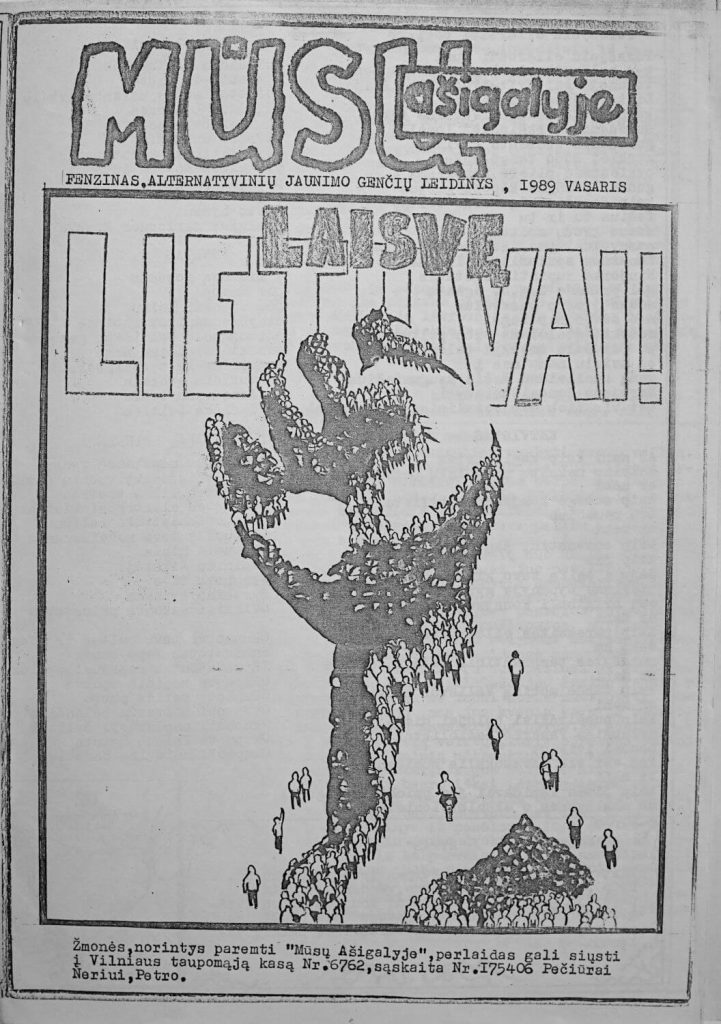

The illegal anti-Soviet fanzine Mūsų ašigalyje (“At Our Pole”) was published, written, photographed, copied, and distributed underground in 1988–1989 by Nėrius Pečiūra, Vikintas Darius Šimanskas, Ernestas Volodzka, Giedrius Burkšaitis, Vytautas Šumacheris, Gediminas Mačiulis, Nijolė Stabingytė, Vaidotas Žygas, Darius Čumačenka, and others.

Vilnius, February 1989 (personal archive of Nėrius Pečiūra)

On 11 September 1988, while performing in the Vilnius Alumnatas courtyard, Atsuktuvas tossed a stack of Mūsų ašigalyje (“At Our Pole”) – the first fanzine – into the crowd. The publication demanded freedom for music and Lithuania.

“We are not vagabonds. The Fatherland is a specific geographical concept. This is my city, my street, my home,” wrote the punk newspaper.

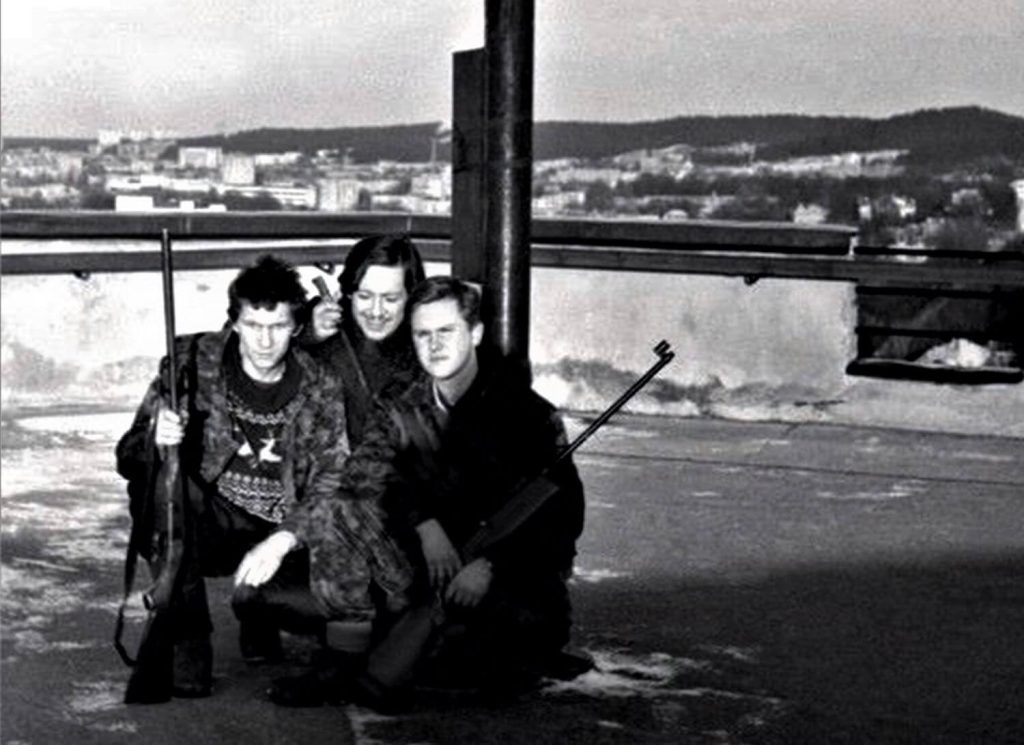

The punks didn’t lose their fighting spirit even in March 1990, when Lithuania declared independence. On those crucial winter days in 1991, Varveklis, armed with a home-made rifle, guarded the Lithuanian flag on the Tower of Gediminas.

In his opinion, punks were not a destructive element of society, but rather – a creative one. Nėrius Pečiūra attributes punk culture in a broad sense to global art currents such as expressionism, impressionism and Dadaism. There is a lot of everything in this culture, and it continues to develop to this day.

Vikintas Darius Šimanskas-Varveklis (left) with his brothers in arms at the Tower of Gediminas during the turbulent days of the January Events, protecting the symbol of Lithuania’s Independence and statehood – the Lithuanian tricolour.

Vilnius, January 1991. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Vikintas Darius Šimanskas)