The Rebellion of Youth (1964–1991)

POLITICAL RESISTANCE

The goal of the Lithuanian Liberty League is the restoration of an independent Lithuania. […] All residents of Lithuania can consider themselves members of the LL League if they fight (as best they can) for the goals of the LL League.

From the Lithuanian Liberty League Declaration of 15 June 1978

The non-political subculture was characterised by youthful idealism and maximalism. Some young people decided to fight directly against the communist system that was being imposed on them by strangers and join the unarmed resistance movement or the political organisations that were being founded or re-established after the repressions of the occupants. The political situation in occupied Lithuania did not change in the 1960s. In 1961, the KGB uncovered Laisvoji Lietuva (“Free Lithuania” – an underground organisation at the Vilnius 16th Secondary School started by the young Vladas Šakalys), and most of its members were given long prison sentences. Similar organisations were also active at other academic institutions and companies. Young people were demanding independence – they handed out flyers, wrote slogans on the walls, raised the Lithuanian tricolour and tore down the flags of the occupants, and distributed banned literature. Individual members of non-political subcultures interacted, and some collaborated with people in the unarmed resistance; they helped them spread underground literature, celebrated national holidays, and visited the graves of celebrated Lithuanians. When the Prague Spring began in Czechoslovakia in 1968, the attempt of the Czech people to escape from the imperial grip of the USSR became an impetus for stronger resistance in Lithuania. The self-immolation of Romas Kalanta on 14 May 1972, which turned into mass manifestations of youth protest in Kaunas, announced to the world that Lithuania had neither been broken, nor come to terms with slavery. The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, which came out just a few months prior on 14 March, not only shed light on the violations of the rights of believers, but also revealed other wrongdoings in Lithuania and defended the member of the resistance who were being persecuted. The cultural constraints and repression of the Cheka that swept through Lithuania did not stifle the nation’s aspirations for liberation. Young people were eager to do what they could to “sting” the regime, shake its foundations, and start “revolutions”, small or large.

Young people at a march organised by the Lithuanian Liberty League, Young Lithuania and Geneva-49 to protest compulsory service in the occupant Soviet Army. On the right is Lithuanian Liberty League member Darius Kavaliauskas, and on the left is Nerijus Kavaliauskas. Behind them, second from the left, is partisan Leonas Laurinskas-Liūtas, who, on 14 June 1988, was the first to publicly raise the flag of the state of Lithuania after the national revival began.

Vilnius, 1989. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Darius Kavaliauskas)

A group of pupils got together at the Antanas Vienuolis Secondary School in Vilnius. The schoolchildren assisted the clergy during Mass at Church of St. Nicholas, were in contact with Viktoras Petkus and Antanas Terleckas – two well-known resistance fighters, and lit candles in Rasos Cemetery for historical figures and Lithuanian soldiers who died in the Freedom Struggles. The young people did not give in to despicable acts and refused to give false testimony to the KGB interrogators against Viktoras Petkus. In 1976, Julius Sasnauskas, Vytautas Bogušis, Andrius Tučkus, Kęstutis Subačius and Algirdas Masilionis were expelled from the 11th grade without the right to continue studying at a full-time school. Most of them were not allowed to study at institutions of higher education, and three of them were taken as recruits into the Soviet Army. Together with experienced members of the resistance, Julius Sasnauskas published the illegal newspaper Laisvės šauklys (“Herald of Freedom”), and edited and published Vytis, which was another underground periodical. The young resistance fighters became active members of Lietuvos Laisvės Lyga (“Lithuanian Liberty League”), which, after being formed in 1978, was the last resistance organisation and the first political organisation of the national liberation movement. The league created and distributed documents, sent letters to representatives of the Soviet government and international organisations, and protested against Russification, the savage treatment of members of the resistance, and the political abuse of psychiatry.

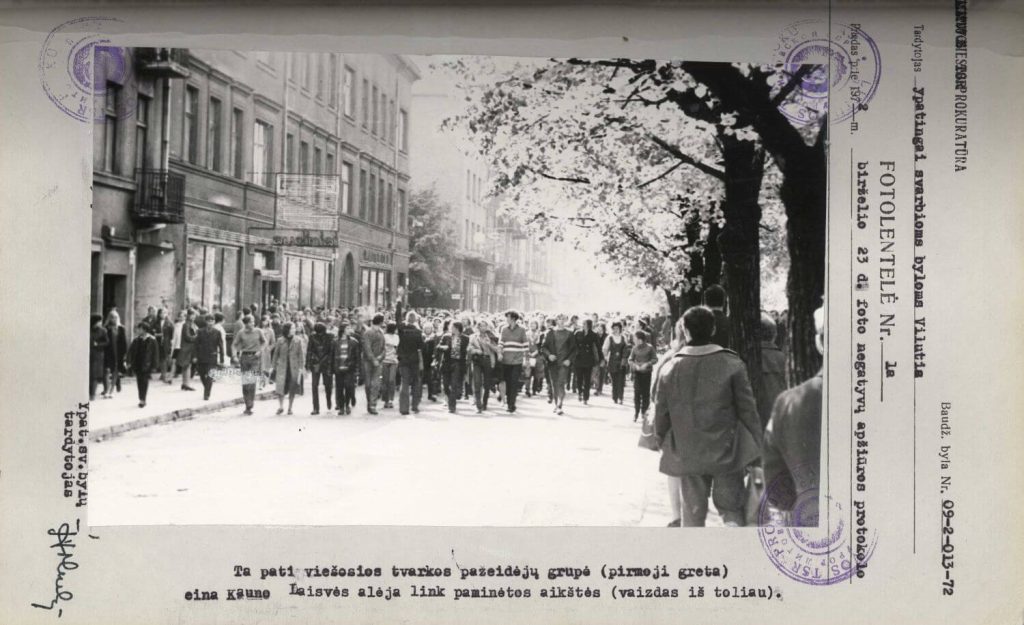

Photo evidence No 1a in the criminal case brought by the KGB against the participants in the youth protest march that took place on Laisvės Avenue in Kaunas on 18 May 1972 after the self-immolation of Romas Kalanta. In those turbulent days, more than 3,000 demonstrators took to the streets, and over 7,000 militia volunteers, militiamen and soldiers were brought in to suppress them. The protesters were caught, shaved bald, interrogated and beaten; their documents were confiscated, and the more active ones were thrown out of schools, sent for compulsory service in the Soviet Army, or imprisoned. The demonstrations gave a strong impetus to civil anti-occupation resistance. They showed the world that Lithuania had not been broken.

Kaunas, 1972. Photo author unknown (Lithuanian Special Archives)

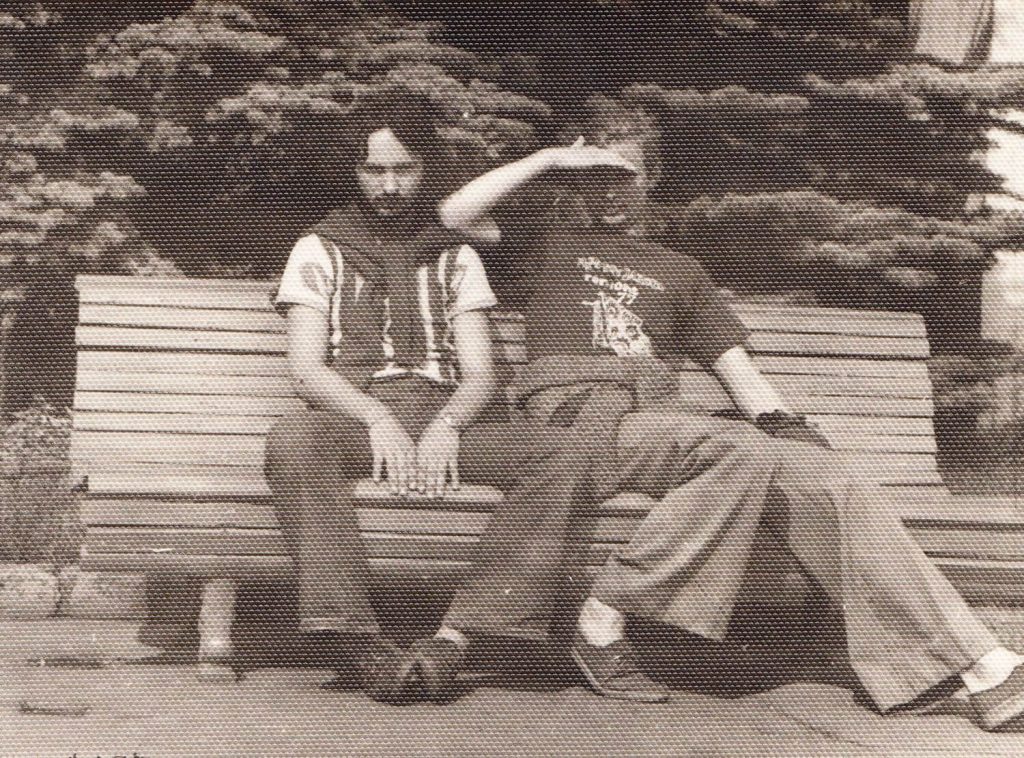

Architect Gintautas Tiškus (left), who accompanied the Lithuanian resistance “courier” Liutauras Kazakevičius (right) to visit Russian dissidents in Moscow. Youth legend Liutauras Kazakevičius – a signatory of the Baltic Appeal and a walking library and encyclopaedia.

RSFSR (Moscow), late 1970s. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Gintautas Tiškus)

How many Lithuanian youths were terrorised by the occupation authorities? It is impossible to say how many of them participated in the political resistance. The LLL, which raised the idea of an independent state, announced that all residents of Lithuania can consider themselves members of the LLL if they fight for the league’s goals. What Lithuanian didn’t dream of an independent state? In addition to the LLL, there were resistance movements across the political spectrum in Lithuania. The underground published a variety of periodicals, including Aušra (“Dawn”), Dievas ir Tėvynė (“God and Fatherland”) and Perspektyvos (“Perspectives”), among others. Undeterred by the repression, many young people participated in the anti-occupation protest rally that was held at the Adam Mickiewicz Monument in Vilnius on 23 August 1987. Their faces showed no fear. Less than a year later, even more of them took to the streets of Vilnius on 16 February – Lithuanian Independence Day – despite the hysteria raised by the authorities. Militiamen chased them off, beat them with rubber batons, crammed them into buses, and took them to jails or away from the city. Young people also took part in the 22 May 1988 rally that was organised by the LLL to commemorate the mass deportations to Siberia but was broken up by the authorities. That summer, the Reform Movement of Lithuania held thousands-strong rallies across Lithuania that no one broke up. The LLL rally held in Vilnius’s Gediminas Square (now Cathedral Square) on 28 September 1988 to condemn the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which were signed on 28 September 1939 and led to the occupation of the Republic of Lithuania, ended differently. In 1989, youth protests began against Lithuanian men being taken for compulsory service into the army occupying Lithuania. The LLL, Young Lithuania and Geneva-49 organised massive rallies, marches and other protest campaigns demanding that the Russian army leave the territory of Lithuania. After taking over this campaign, the Reform Movement of Lithuania collected 1,650,000 signatures for the withdrawal of the occupying army. Lithuanian men began to desert and go into hiding.

Lithuania would not have been liberated if this strong stream of youth movements had not joined the resistance.

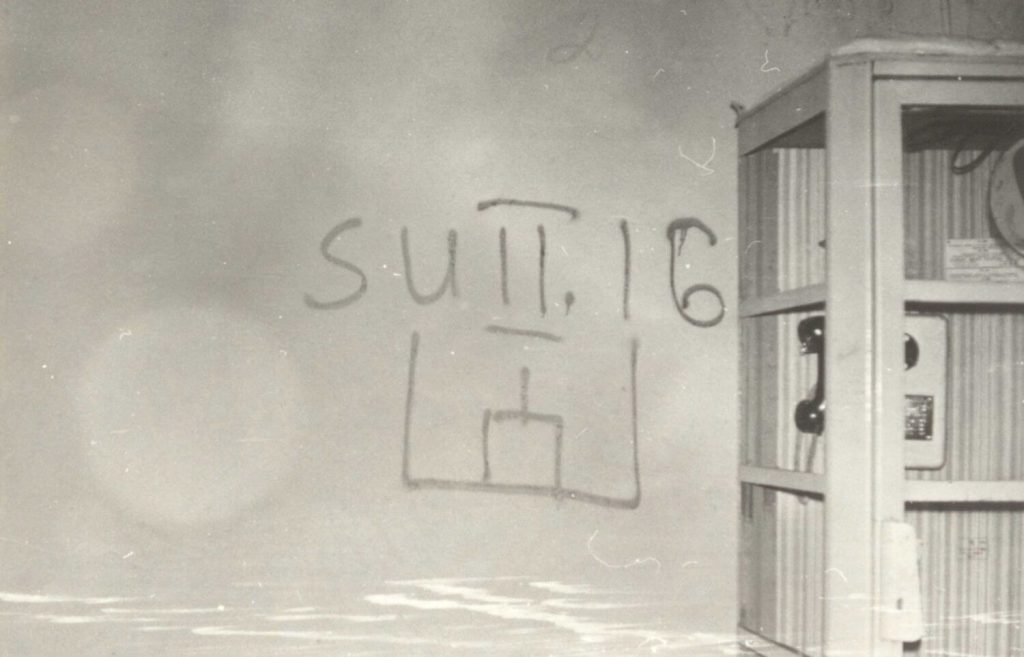

“Su II. 16” (“Happy II. 16”, i.e. 16 February, Lithuanian Independence Day). On the eve of 16 February 1983, the KGB recorded an “unacceptable” inscription on a wall in Vilnius between buildings No 10 and 12 on what was then J. Paleckis Street.

Vilnius, 15 February 1983. Photo author unknown (Lithuanian Special Archives)

The resistance fighter Julius Sasnauskas in exile. In his youth, Julius grew his hair long, admired rock music, and immersed himself in the world of books. He met Viktoras Petkus, Antanas Terleckas and other members of the resistance. He was expelled from the Antanas Vienuolis Secondary School for his views. In 1977, he was involved in the publication of the underground newspaper Laisvės šauklys (“Herald of Freedom”). After compulsory service in the Soviet Army, he took up active political activity. While working as a guard at the Church of Sts. Johns in Vilnius, he printed the first underground issue of Vytis on a typewriter at night. Sasnauskas helped prepare protest statements regarding human rights violations, persecution of the Church, the falsification of history and the destruction of cultural monuments, and also wrote and edited texts. He was one of the founders and activists of the underground organisation Lithuanian Liberty League, and one of the authors and signatories of the Baltic Appeal. He was arrested in 1979 and convicted of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda in 1980. He was imprisoned in the KGB prison (the LSSR KGB jail) in Vilnius for 18 months, and then exiled for five years to the village of Parabel in the Tomsk Region in Western Siberia, where he worked as a plumber, stoker and loader. In 1987, he participated in the Lithuanian Liberty League’s first public anti-occupation rally at the Adam Mickiewicz Monument.

RSFSR (Parabelsky District, Tomsk Region), 1984. Photo author unknown (Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights)

Leokadija Ratautaitė holding the tricolor flag raised above helmets of the special-purpose occupying army. On September 28, 1988, in Vilnius’s Gediminas Square (now Cathedral Square), the Lithuanian Freedom League organized a rally condemning the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed on September 28, 1939. The authorities brutally dispersed the demonstrators. The event became known as the “Banana Feast” – a sarcastic nickname referring to the rubber batons used by the militia.

Vilnius, 28 September 1988. Poster published by Vyturys Publishing House (personal archive of Gintautas Terleckas)

On 28 September 1988, in Vilnius, at Gediminas Square (now Cathedral Square), the Lithuanian Liberty League organized a rally to condemn the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed on 28 September 1939. The authorities violently dispersed the participants, including a large number of young people. The event became known as the “Banana Feast” – a sarcastic nickname referring to the rubber batons used by the militia.

Vilnius, 28 September 1988. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Gintautas Terleckas)