The Rebellion of Youth (1964–1991)

On the Road

This was the great miracle of the System – hitchhiking. When you go out, stop a car and drive off. […] the most important thing is that you feel like you’ve taken off something dirty, something so filthy, because you’re going out on the road, free. It was crazy, but it was so good. […] That road, it… first and foremost gave you a sense of liberation – a very big and deep one. Of belonging to no one. You truly belonged to yourself, and no one else – not a party, not an organisation, not your father, not your mother, not your grandmother, not your grandfather, no one. You just were, simple as that.

Poet Romualdas Trachimas-Tomas Mučius

Hitchhiking didn’t always mean stopping cars on the road – it could also be on a passenger train, usually without a ticket, or in the freight wagons. There were times when you had to travel with a hook attached to it, or when you would go on foot – after all, you can’t just stand there. The Lithuanian translation of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road came out in Lithuania in 1972 and was the first piece to be published by this Beatnik writer in the entire Soviet Union. The book became the freethinkers’ Bible. Feeling like Kerouac’s heroes, young people would go out and hit the road, where every second could take them in a new direction – away from home, from their parents and from the corruption of the system that had become embedded in the homeland. The same system still existed in the USSR, but while out hitchhiking, a person could become detached from its rules and constraints for a while, leaving them on the road with the buildings, poles and trees disappearing in the distance.

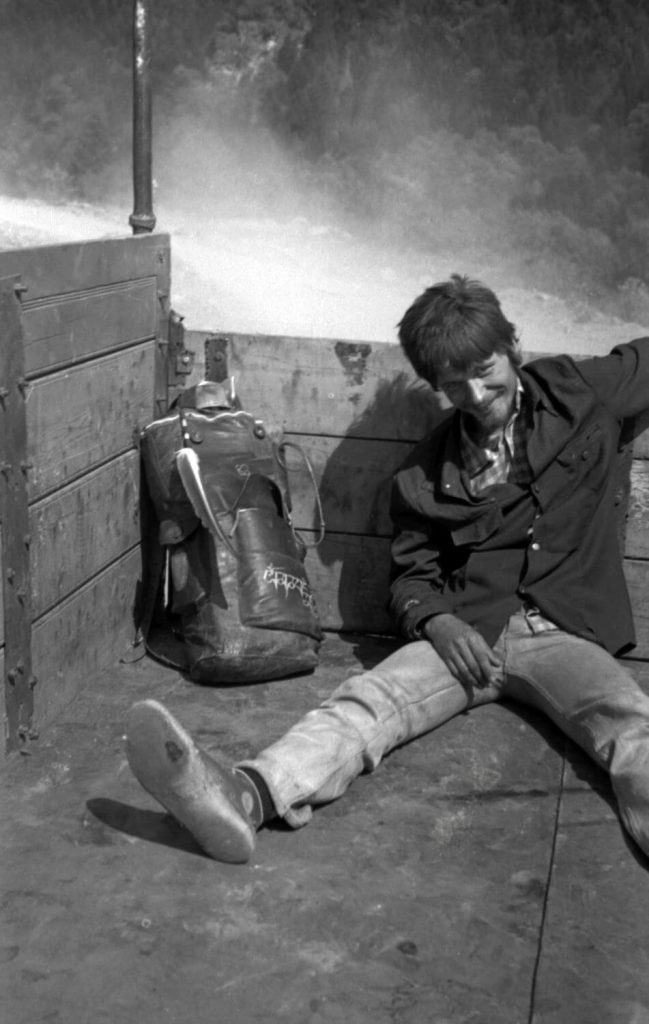

Hippie Jurijus Tolčkovas-Guliveris, a close friend of rebellious artist Gitenis Umbrasas, riding in a freight train car across the vast landscapes of Central Asia. He later died in the mountains of the Mamison Pass in Ossetia (now part of the Republic of North Ossetia–Alania in the Russian Federation and the Russian-occupied territory of South Ossetia).

RSFSR, early 1980s. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Gitenis Umbrasas)

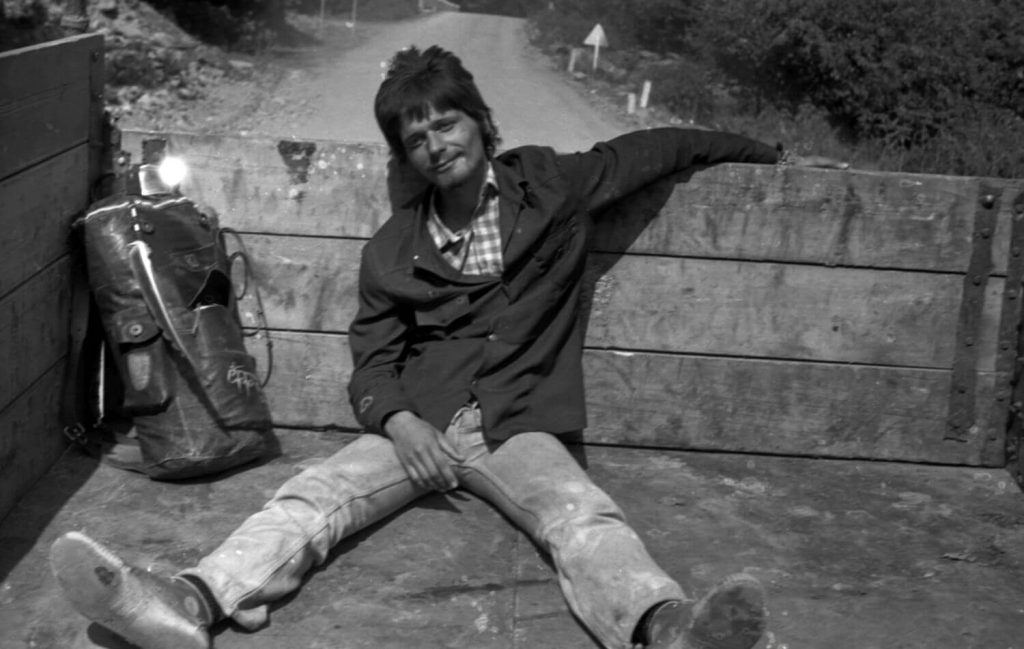

Artist Gitenis Umbrasas (first on the right) and his friends setting up a campsite at the Mamison Pass near the symbolic border between the Russian SFSR and the Georgian SSR (now the Republic of North Ossetia–Alania in the Russian Federation and Russian-occupied South Ossetia).

USSR, early 1980s. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Gitenis Umbrasas)

Artist Gitenis Umbrasas (first on the right) and his friends setting up a campsite at the Mamison Pass near the symbolic border between the Russian SFSR and the Georgian SSR (now the Republic of North Ossetia–Alania in the Russian Federation and Russian-occupied South Ossetia).

USSR, early 1980s. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Gitenis Umbrasas)

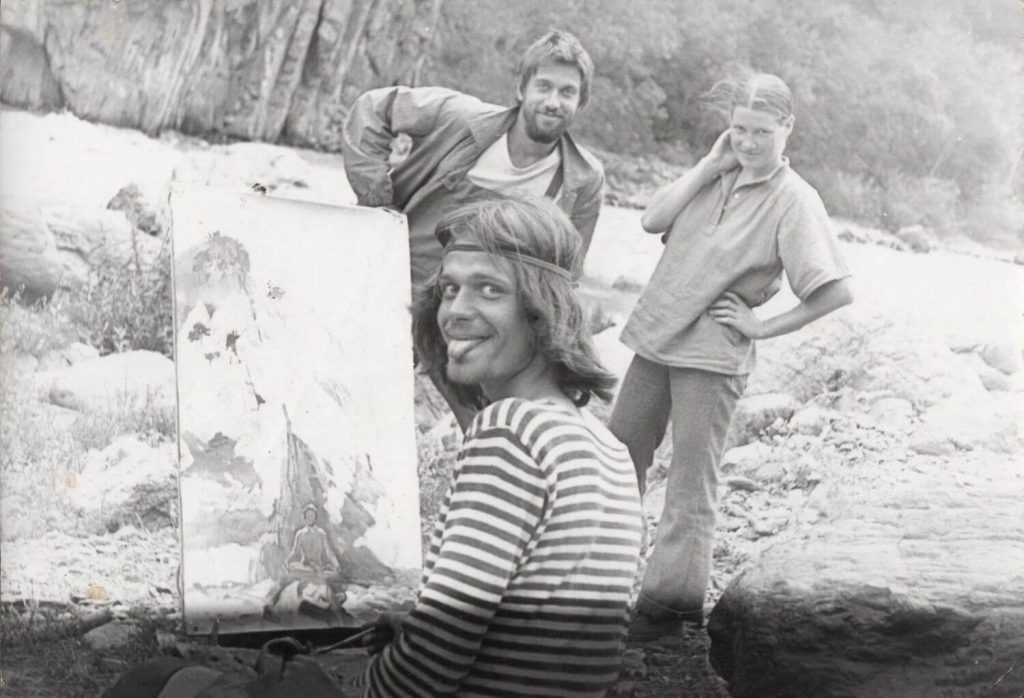

Artist Gitenis Umbrasas painting the Caucasus Mountains at the Mamison Pass near the symbolic border between the Russian SFSR and the Georgian SSR (now the Republic of North Ossetia–Alania in the Russian Federation and South Ossetia, occupied by the Russian Federation). Further away – Gitenis’s yoga-practicing friends from Moscow.

USSR, early 1980s. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Gitenis Umbrasas)

Hippie youth at the Mamison Pass in the Caucasus Mountains near the border between the Russian SFSR and the Georgian SSR (now the Republic of North Ossetia–Alania in the Russian Federation and South Ossetia, occupied by the Russian Federation).

USSR, early 1980s. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Gitenis Umbrasas)