The Rebellion of Youth (1964–1991)

HIPPIES – FLOWER CHILDREN

The wind carried me,

And it was the wind that sowed me.

The rivers are my sisters,

The trees are my brothers.

Birds are perching in the trees,

Fish are swimming in the river.

And I’m almost like a tree,

And I’m just like the wind.

Just please – don’t be angry

That it turned out this way.

Nieko man nereik (“I Don’t Need Anything”) by Antanėliai

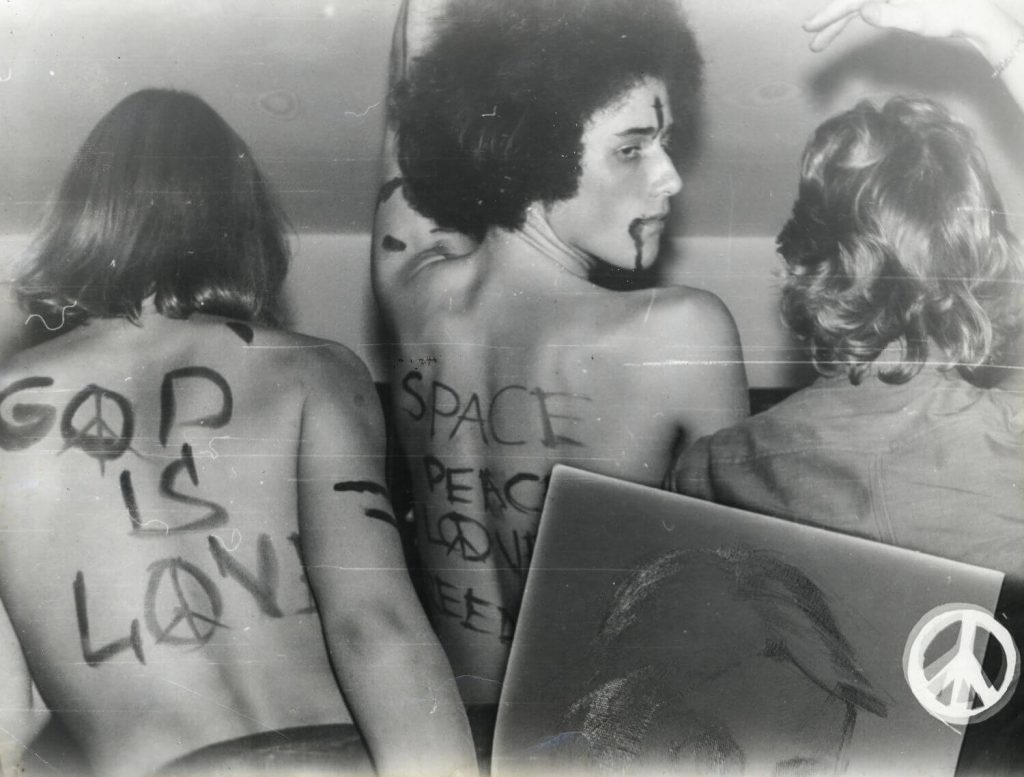

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, amidst the social stagnation of the Brezhnev era, the song Nieko man nereik (“I Don’t Need Anything”) by the rock band Antanėliai was playing in Lithuania. The hippie movement, which began in the United States in the early 1960s, had reached the closed empire of the USSR. According to Romualdas Trachimas, the ideas of love, peace, flowers and light were intertwined with the idea of “flower children”. Man is a child of nature – free as the wind, carrying himself, sowing himself – almost like a tree where the birds of freedom perch, with rivers, his sisters, flowing beside him. Faced with an absurd system imposed by strangers, young people looked for resistance in nature, because this is what helped them and the world not to lie, not to live a lie, not to play with a lie. There was no other way to live. Such was the “[…] young people’s rebellion. Rebellion to be themselves, rebellion to create, rebellion to resist what cannot be. And that is completely natural. It’s probably in the nature of every person, especially young people, to change the world, to change it as it is, because the world is not perfect,” recalls Janina Matekonytė-Antanėlienė about her husband, Kęstutis Antanėlis.

The empty and unjust world of occupation was opposed by fashion, music, poetry and art, by a way of life and ignoring the Soviet system. It was a return to what was eternal and valuable. In the Soviet Union, the hippie movement was different than in the West. In persecuting the “flower children”, the Soviet political regime banned their forms of expression (living in communes, avoiding “work useful to society”, holding hippie gatherings and festivals). Young hippies gathered in free, non-committal, closed groups that were not bound by rules. These groups brought together like-minded people who had voluntarily “thrown themselves out” of society, but who had not strayed far from it. The mysterious world beckoned, attracted, enticed. What was new, forbidden and not yet experienced was especially tempting. There was a desire to know, to touch, to understand. The carefree days of youth intertwined with an appetite for reading and interaction. Young people learned to express their thoughts and defend their truth boldly, freely and without external pressures. This display of “lost” youth disheartened and annoyed the arrogant KGB officers who were feared by everyone. The regime cracked down. Some of the hippies did not work anywhere. For them, poetry, creativity, thinking and life itself were work. Everything else was a restrictive framework. These people got bangladesh – an article of the Penal Code that made “parasitism” a criminal offence. Like other young men, hippies were drafted into the Soviet Army. For a person not used to falling into line, the practices of муштра (a system of harsh military discipline) and дедовщина (the informal hazing and abuse of new recruits) posed a risk of mental and physical abuse. Even outside of the army, you could be arrested, beaten or shaved bald by the blue militiamen – icons of the spirit of the mature socialist era – just for appearing in a public place with “your symbols” (like long hair or bell bottoms).

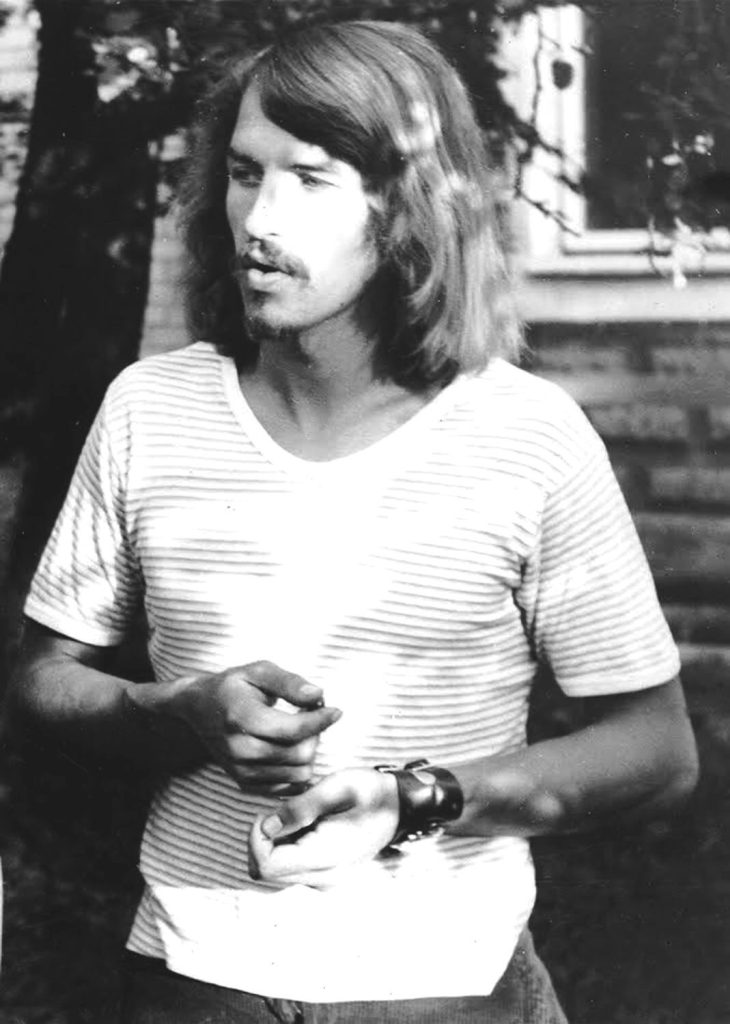

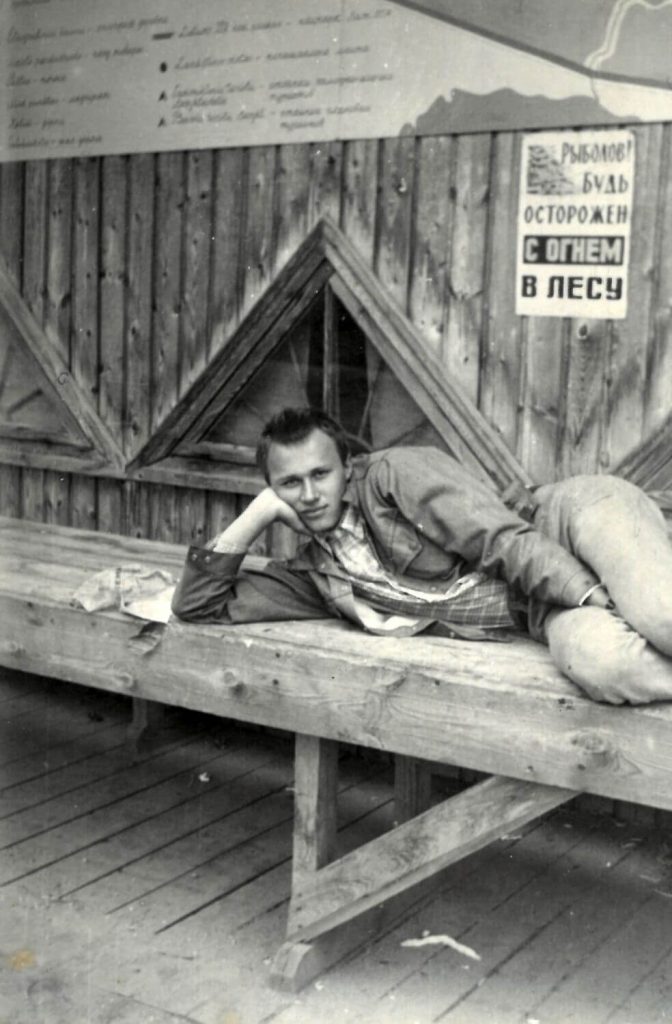

Prominent Lithuanian hippies by the Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Church of Vytautas the Great) in Kaunas. From left to right: Valerijus Viksmanas-Fikusas, Aleksandras Jegorovas-Džyza (1952–2014), Alvitas Taunys-Guru (1949–1979).

Kaunas, 1970–1972. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Arūnė Taunytė)

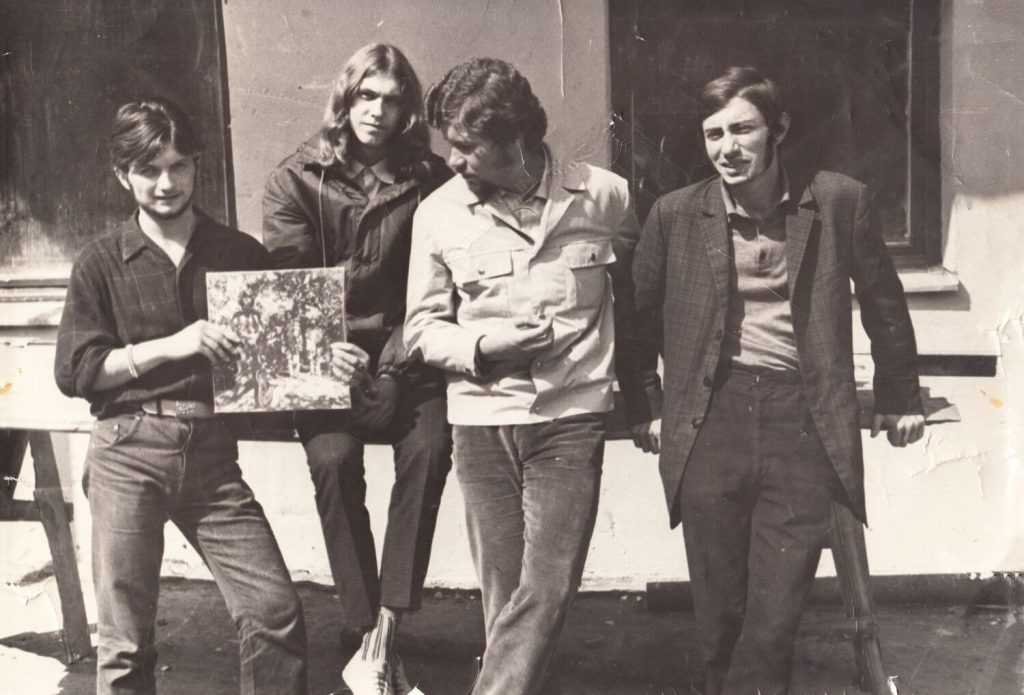

Lithuania’s most active hippies. From left: Lionginas Leščinskas-Leščius, Aleksandras Jegorovas-Džyza (1952–2014), Alvitas Taunys-Guru (1949–1979), Valerijus Viksmanas-Fikusas. Leščinskas is holding a western rock record album – a highly valued item among the young people at that time. These records fascinated them with the inexplicable magic of their music and their artistic covers.

Kaunas, 1970–1972. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Arūnė Taunytė)

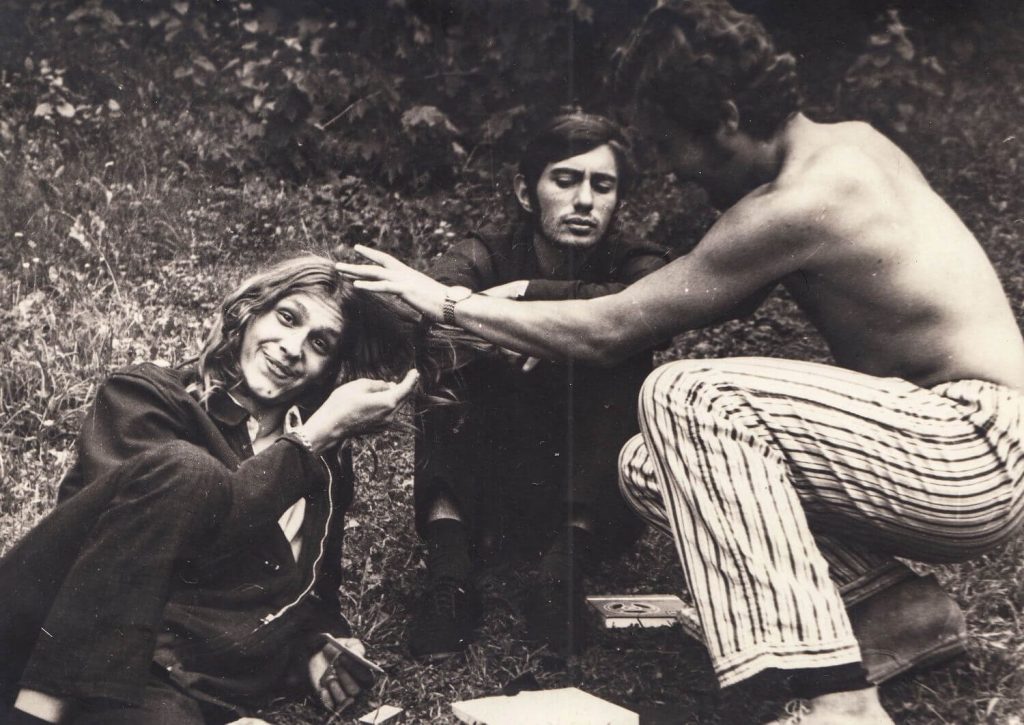

Famous Lithuanian hippies. From left: Aleksandras Jegorovas-Džyza (1952–2014), Valerijus Viksmanas-Fikusas, Alvitas Taunys-Guru (1949–1979). Aleksandras was a true hippie legend – he was the life and soul of the party and took part in all of the big hippie events. After the 1972 self-immolation of Romas Kalanta, he participated in the Kaunas protests and fell out of favour with the authorities. He was repeatedly interrogated by KGB operatives, and eventually arrested and locked up in a the “loony bin” (which is what they used to call the psychoneurological dispensary) for some time. He was a member of the bands Chairs and Nuogi ant slenksčio (“Naked on the Threshold”), among others, and was one of the founders of the blues band Senas Kuinas (“Old Nag”). He was awarded the January 13 Commemorative Medal in independent Lithuania.

Occupied Lithuania, 1970–1972. Photo author unknown (personal archive of Arūnė Taunytė)

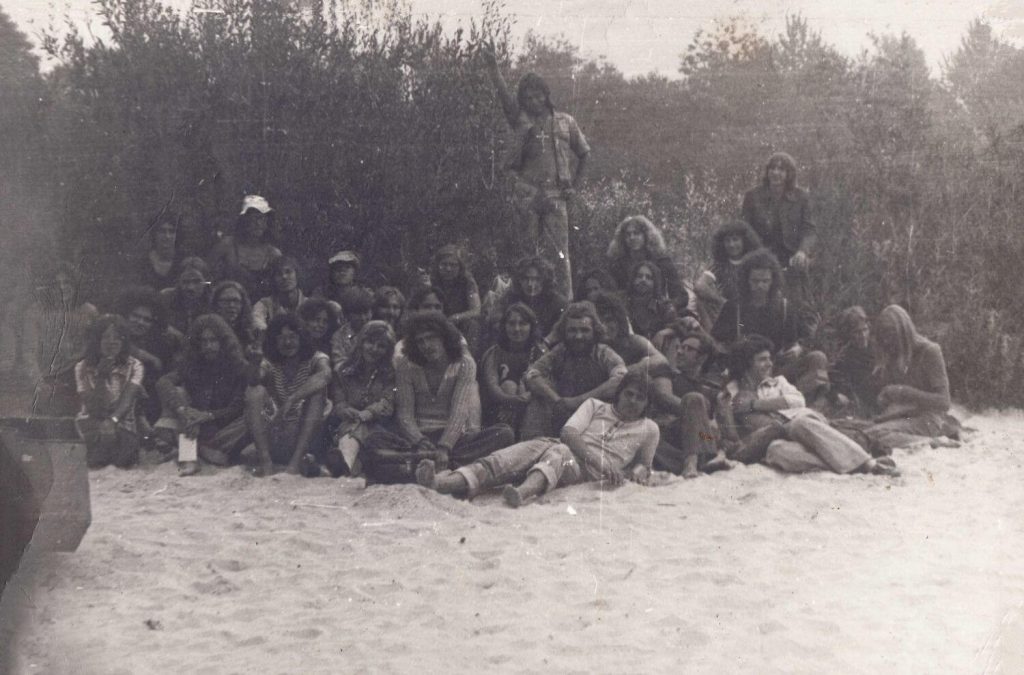

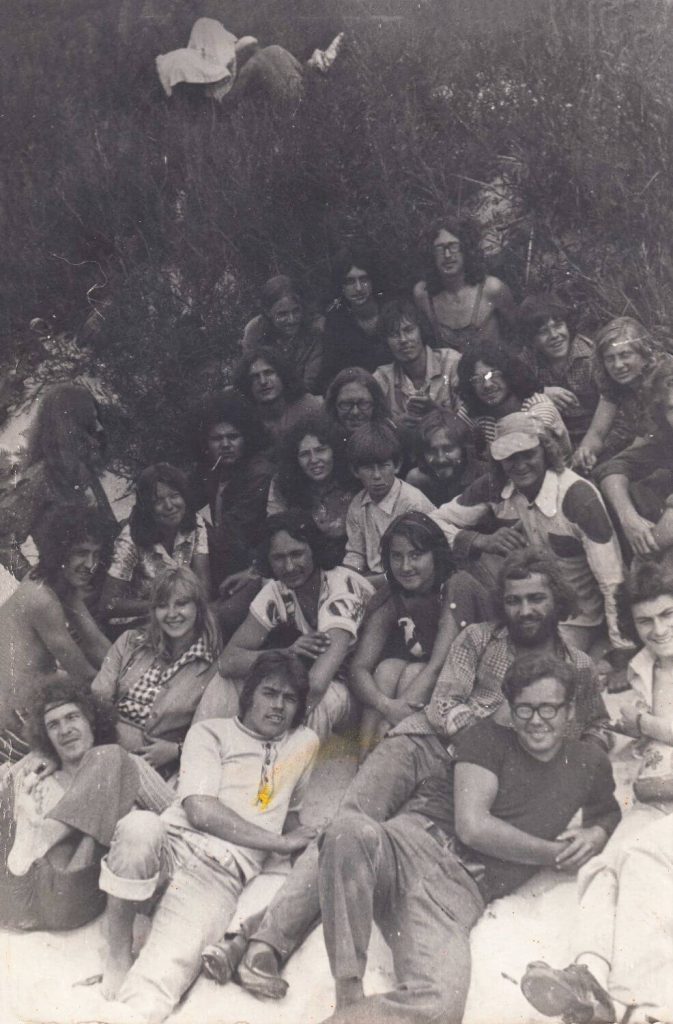

A photo of unidentified young supporters of the hippie movement that was found among the documents of the Kaunas City branch of the USSR Committee for State Security (KGB). The hippie communes that were emerging in Lithuania were broken up by the KGB and their members were persecuted.

Occupied Lithuania, 1978–1990. Photo author unknown (Lithuanian Special Archives)