After attacking a sovereign state on the 24th of February, 2022, the imperialist Russia is continuing the destruction of Ukrainian nation that it started long ago. Nations that are not prepared to bow down to the slavery, imposed by the Kremlin chauvinists, are warned for an even more horrible existence. Moscow’s aggression turned the world upside down, breaking the standards of understanding a supposed balance. In an attempt to protect itself, the civilisation is charting new political directions, turning to the past for wisdom and strength.

History repeats itself in cycles. What is happening already occurred before… During World War II, while suppressing the guerrilla war in Ukraine and Lithuania, that same Russian army carried out terror and genocide on the conquered nations. The people of older generation are aware of this force all too well. For Lithuanian families, those 50 years of the occupation meant that their men were subject to a forced conscription.

It can’t be forgotten.

Sources

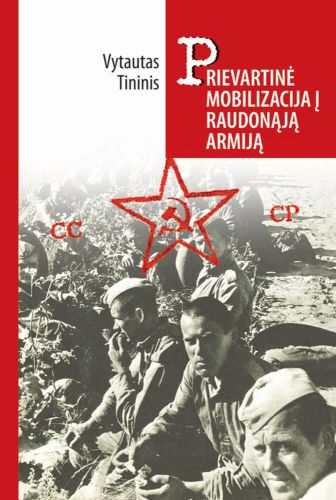

The repression, experienced by Lithuanian men, became a subject of several documentaries; there were some individual exhibitions as well as memoirs and other testimonies published on this topic. In 1991, writer Vytautė Žilinskaitė wrote a book entitled “Prašė neverkti” (“Asked Not to Cry”), where she compiled the stories she had collected from the relatives of the conscripts, killed and crippled in the Russian army. In “Rekrūto atsiminimai” (“Memories of Recruit”), priest Robertas Grigas brilliantly described his own hardships as a soldier, who refused to take an oath to the military power. The late Afghanistan War veteran Zigmas Stankus left two evocative memoirs: “Kaip tampama albinosais” (“How to Turn into an Albino”) and “Miražas” (“The Mirage”). In his short book entitled “Lauk, okupantai!” (“Occupants Out!”), former soldier Petras Algis Mikša shared the memoirs of the recruits who participated in the 1968 occupation of Czechoslovakia. In his photobook entitled “Užmirštas” karas“ (“The ‘Forgotten’ War”), Vytas Lukšys, a conscript who survived the horrors of Afghanistan, tells about the tragedy through the photos of those who fought. “Sustingęs laikas” (“Frozen Time”) presents a list of the soldiers from Lithuania who died in Afghanistan.

The past, revealed in the sources, takes on new meanings in the context of the Ukrainian war. It seems to invite us to reflect anew on what was and what is. The Ukrainians’ courage and determination expose old propaganda lies, and help find the right words in the tangle of concepts and myths, imposed by strangers and created by ourselves.

In the exhibition, the fragments from the already published sources are accompanied by the new ones: filmed excerpts from the stories of the contemporaries, and copies of the photos and letters from the personal archives and the funds of the Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights. The creators of the exhibition sought to remind us of the things that may have already been forgotten, and to show what has not been seen, what is not known.

Occupation

The occupation of Lithuania turned the ordinary world upside down. The carriers of the doctrine of communism erased and destroyed traditional values, and then filled the resulting void with an absurd order. Lithuanian men, wearing the uniforms of their conquerors, defended their captivity for years, and helped the monster of Russian imperialism to grow and prosper. Russian dissident Vladimir Bukovsky compared the USSR to a concentration camp, and its army was a part of this formation. It was a place where cynicism and contempt for a human being flourished, right alongside the claims of utopia. In the words of philosopher Juozas Girnius, throughout the system, slavery was diabolically worshipped as freedom, while freedom was looked down upon as slavery. After being drafted into the occupant army, each Lithuanian recruit endured the new order in his own way. Their different talents and characters as well asdifferent political circumstances of the time, determined the individual fate of each of them in the military environment.

Even today, the narrative that “the Soviet Army was a school of masculinity” lives on. In 2002–2004, the courts of independent Lithuania and some members of the Seimas still made no distinction between the slavery, imposed by the occupants, and the military duty to the Fatherland. Some soldiers got lucky and did not have any major tragedies in the Soviet Army. However, this fact does not change anything. It was a part of the terror and genocide of the nation. The illegal coercion that went against the international law destroyed the destinies of the majority of families.

Losses

Lithuanian soldiers died in Red Army units during World War II

Red Army deserters and draft evaders (not partisans) were killed in 1944 and 1945

Išėjusi dvidešimtmečių jaunystė (The Foregone Youth of Twenty-Year-Olds), Vilnius, 2002, p. 28

men from Lithuania were injured while serving in the Red Army from 1945 to 1991 according to the primary data collected from the questionnaires

Testimonies of the Past

The letters and photos that soldiers sent home did not reflect the entire life of the men conscripted by force. Fearing censorship, the soldiers avoided talking about what the occupation authorities were hiding, or opted not to mention how they were feeling in an effort to protect their loved ones. But even then, phrases or details in photos that gave away the dark side of being a soldier would still reach home.

Unable to stand the humiliation and bullying, a soldier would sometimes give in and turn to his letters for some compassion and advice. Parents would try to save their children by writing complaints to the highest occupation authorities. However, these complaints rarely changed anything.

In some Soviet units, especially during military invasions of other countries, it was forbidden for recruits to take pictures or indicate their location. Yet even then, they still managed to capture the moments of their lives. Some of those moments even reached their Fatherland. The grey photos reveal the dull routine of the military life, “embellished” by a tank, standing nearby, or senseless slogans of a propaganda poster.

However, even photographs like these leave traces, thus becoming testimonies of events – a reflection of the human spirit and its transformation. As if the spirit of a free man, born in Independent Lithuania and not destroyed by a foreign system, is shining through the glass of a window, while rows of uniformed soldiers, who have lost their individuality, line up elsewhere.

The memories of service in the occupier’s army originated in present-day Lithuania. These testimonies of the past are a valuable part of historical sources.

Exhibition

The exhibition is structured like a tree, with several branching aspects of forced military service. Their descriptions and summaries are confirmed by photographs, video footage, copies of printed memoirs, fragments of letters, and other artefacts.

A separate branch of the exhibition is devoted to fragments of the history of military service: conscription in the Czarist Russian Empire, the destruction of the Lithuanian army in 1940, the evolution of conscription in the Communist Russia, the military invasion in other countries, theanti-military protests of the Lithuanian Revival, and the end of the occupation.

“An Alien World”, which is the broadest part of the exhibition, opens with the surrealistic spaces that the communist system dragged a human being into.

Another branch is devoted to the military propaganda. As soon as he was drafted into the army, the conscript was met at the gate of the barracks by tasteless, repulsive propaganda that accompanied him throughout his service. It was meant to subjugate the spirit of the soldier and push the stench of messianism that the USSR spread around the world on him.

The ideology was supported by the mushtra (harsh ordering around) machine that was created by military traditions and underpinned by government laws. In sub-theme “The So-Called School of Masculinity”, a special attention is given to the fate of the people, broken by mushtra, bullying and punishment; to the policy of dividing and ruling soldiers, the aesthetics of the absurd, customs and everyday life. The military service adhered to the principle of “divide and rule”, applied by officers, non-commissioned officers and sergeants. Soldiers were divided into castes according to their time served. The longer a conscript served, the greater his right to the non-statutory treatment of younger soldiers was. The older conscripts oppressed the younger, and the stronger oppressed the weaker. Representatives of different nationalities were put at odds with each other. Everyone spent their short, grey off-duty time in their own way. Some read books and played sports, while others used absurd aesthetics to soothe trauma of bullying – decorating photo albums with drawings of flowers and military equipment, raising the heels of their shoes, and otherwise “embellishing” their uniforms.

Exhibition

“Transformation of Attitudes” branch of “An Alien World” is devoted to the soldiers’ assessment of forced service. It was varied. Some – especially in the first years of Lithuania’s captivity – regarded the Russian army as a foreign force that caused misery, suffering and tragedies. Others equated military recruitment with the senseless loss of years of life and tried to get out of it. However, the men affected by long-time Russian propaganda and the denationalisation policy – especially in the last decades of the occupation – were proud of being drafted and boasted about it.

A separate part of the exhibition entitled “Longing for Home and Freedom” is devoted to the conscripts’ connection to home. Recollections of Lithuania and news from home contrasted with the environment of a foreign land. Letters from the Fatherland became a source of bliss, strength and dreams for most of the soldiers.

The system of conscripting Lithuanian men, introduced by the Soviet authorities, went against the international law. The exhibition displays copies of international acts, declarations and excerpts from the laws of the occupants.

Every family has preserved the memory of the occupation, which lasted for almost 50 years. The harrowing experience of being drafted into the Soviet Army is part of the lives of our husbands, fathers and grandfathers. It is necessary to experience this and rethink it so that we can get rid of the assessment clichés, imposed by the occupants; so that we can feel free and live freely in our Fatherland.