The Rebellion of Youth (1964–1991)

THE TRANSFORMATIONS OF THE REBELLION

There was no other way. They couldn’t adapt and turn a blind eye.

Resistance fighter Kęstutis Subačius

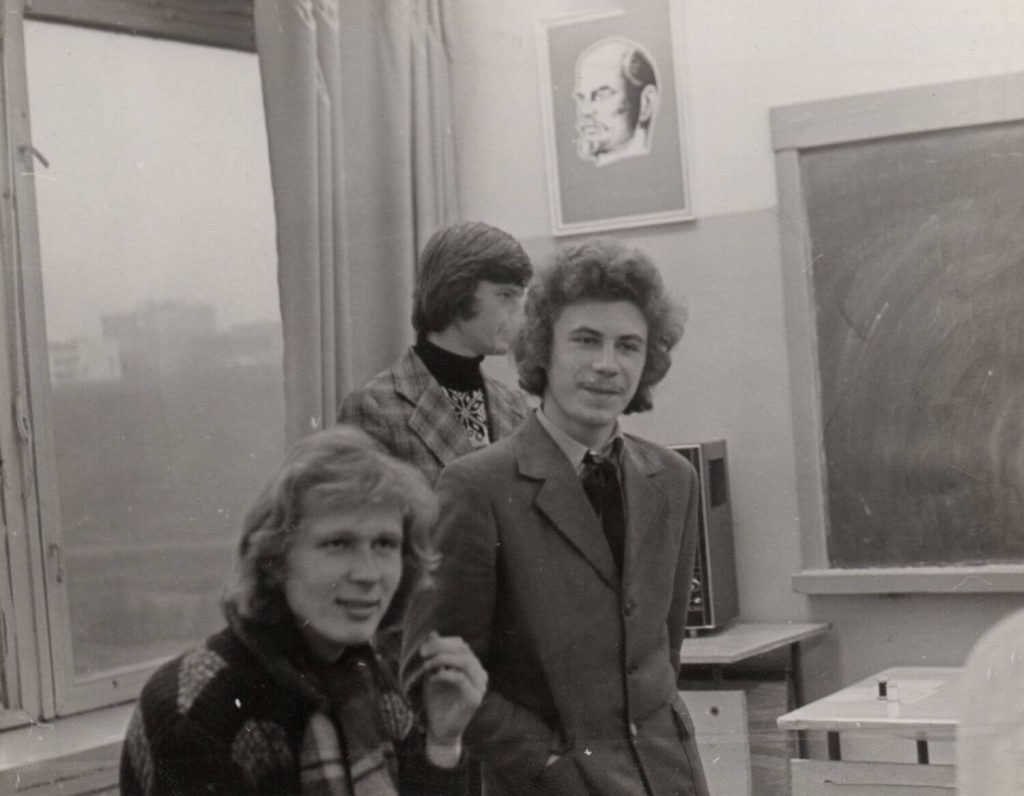

The open genocide of Lithuanians carried out in the first decades of the occupation thinned the ranks of enlightened individuals. To survive, a significant part of the nation was forced to adapt to the coercive system of the conquerors and make ideological and moral compromises. People often declared allegiance to the imposed system in order to foster their culture and defend their language in legal ways. There was hope that when conditions changed, the fading flame of rebellion would reignite in full force. In the 1960s and 1970s, the occupation authorities exercised a bit more caution as they continued to terrorise and persecute the population, violate human rights, and suppress national self-awareness. Their rule of “not blowing against the wind” led to social passivity, duality of personality, levelling of moral values and political immaturity. There was a risk of fully adapting and becoming an active cog of the communist machine, a mankurt without a Fatherland or a memory. Some people did not want to close their eyes – they couldn’t live this way and didn’t know how to adapt. Political prisoners and families of exiles returned to Lithuania. Persecuted by the KGB and subject to repression, the resistance was able to recover and fight. New underground organisations were formed in place of the ones that had been destroyed. In the changing world, the very methods of resistance and forms of protest were transforming. The inhuman Soviet system was strangling the empire itself and was being forced to open up to the world. Members of the nomenclature were allowed to visit other countries. The mostly pro-communist foreigners who came to the USSR had an opportunity to become acquainted with the “paradise” that was being created there. Some of them even made it to Lithuania, which was a particularly closed area (the people of Vilnius first saw these foreigners – who were like Martians to them – in 1957*). Lithuania’s relations with emigrants became closer and closer. No reinforced concrete walls or electronic interference could help the Soviet apparatchiks prevent the spread of free thought on foreign radio waves. The underground press reached Western radio stations, which rebroadcast to the whole world the desire for freedom clearly and directly expressed by the enslaved nations. The West could no longer not hear it and not react. Dissemination of anti-Soviet literature was punishable by imprisonment, but the occupation legal system did not provide any specific punishment for listening to the radio. The word of freedom reached thousands of listeners. It was accompanied by broadcast music. Jazz and rock were characterised by an enormous power of freedom and invited people to rise up.

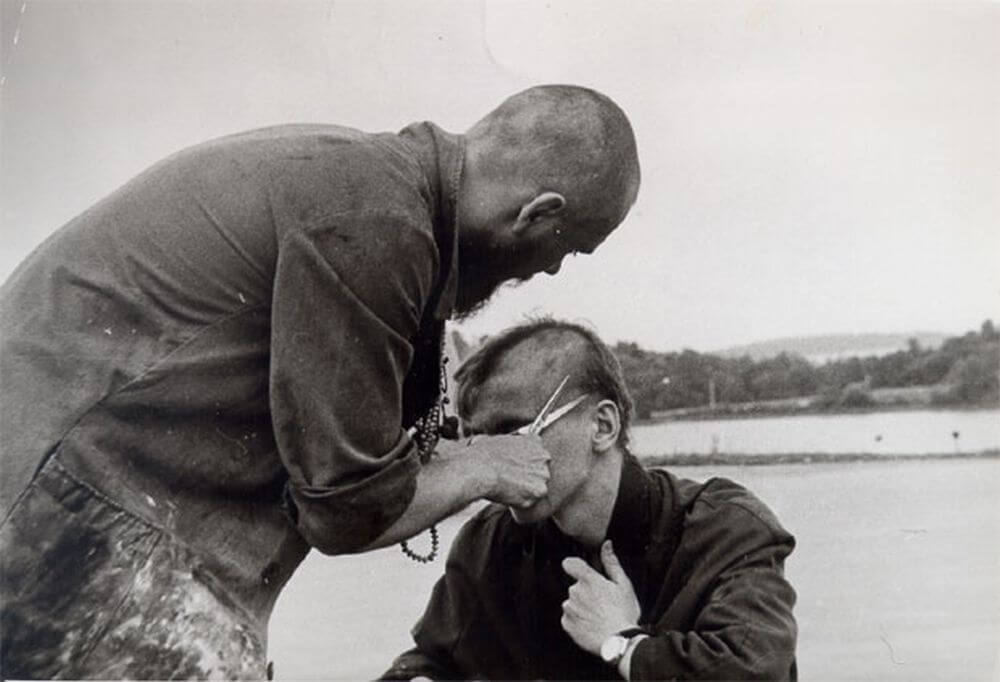

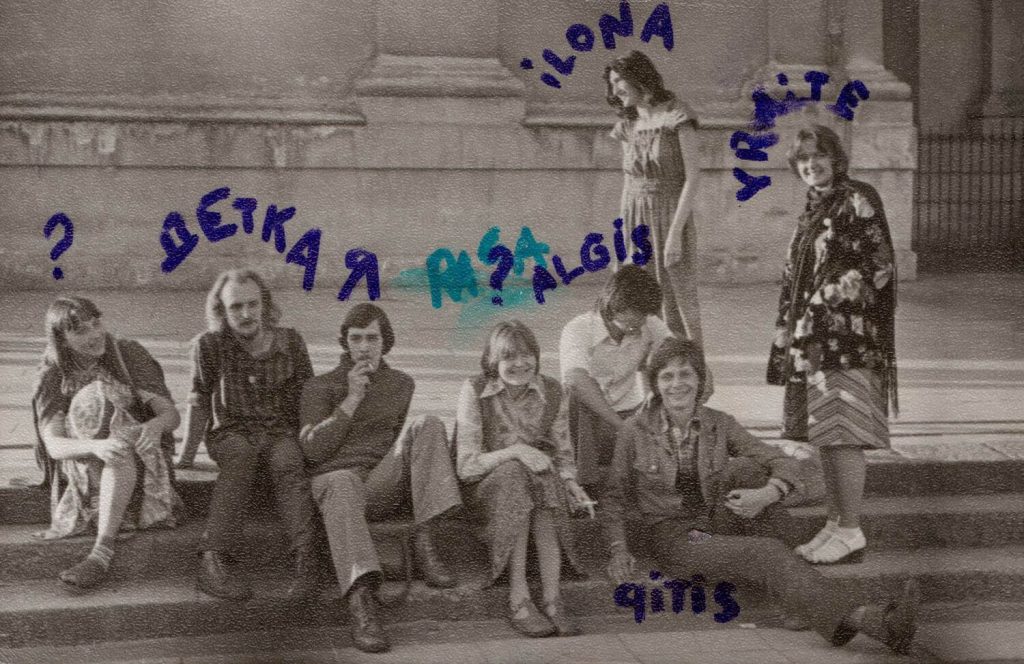

Young people also looked for spiritual resistance in their nation’s past and in its cultural treasures. Despite the interference and persecution of the KGB, various movements developed in Lithuania. “Expeditioners” travelled around Lithuania and talked to locals, collecting historical material, researching customs and traditions, writing down and singing songs, looking after historical monuments and graves of famous people and soldiers, and trying to protect Lithuanian identity in ethnic lands. This activity brought them together into a unique, self-confident, patriotic, educated community. Not afraid of persecution, some young people turned to the search for God, which was attacked in every way by the atheistic system. They assisted the clergy during Mass and read religious literature; some of them became members of the Friends of the Holy Eucharist movement or collaborators and distributors of the underground publication Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, which came out in 1972. Still others sought God in Eastern culture.

Unable to resist the subjugators with weapons, the nation demonstrated its physical and spiritual strength in sports. Fans of Lithuanian basketball or football teams became real rebels, singing patriotic songs that annoyed the government and expressing their protest against the system in other ways. Not only Lithuanian teams were supported. Hockey has become one of the most popular sports. The victories of the Czechoslovakian national team against the USSR’s powerful professional team made up of soldiers turned into a real international celebration for many families glued to their TV screens. In sports, you could root for anyone except the Russians.

Like the previous ones, the youth rebellion during the “mature” era of Soviet occupation was the natural reaction of the vital forces of the nation. Originating from a sense of self-preservation in the most difficult conditions, it became a very important part of the nation’s liberation movement.